The freedom of Spaces

The Architecture of Metro Line 4

Architects: FŐMTERV – PALATIUM – UVATERV Consortium

Text: Eszter Götz

Photos: Tamás Bujnovszky

Fővám tér, architecture: sporaarchitects Kft., photo: Tamás Bujnovszky

It was just about the time of the opening of the new underground line of Budapest when it turned out to provide the capital with an architectural quality experienced never before. Its tracks, above-ground connections and integration into the existing public transport system of the city raises numerous questions but one thing is sure: the overwhelming majority of the deep multi-storey spaces of the stations opening up under the ground obviously offers a simply moving experience in Budapest, moreover, and to be frank, all over Europe in as much as it is unprecedented.

The construction of underground stations feature a unique technology. The „box” is made „up there” above the ground and then lowered into its place through a shaft built especially for this purpose. Then, however, a serious cubic structure remains empty above the top of the station. It is thus logical to ask the question: What could it be used for? A most obvious solution could be to create P+R or underground car parks with different functions. However, this was not allowed by the targeted financiation acquired for this project from the EU in a contest.

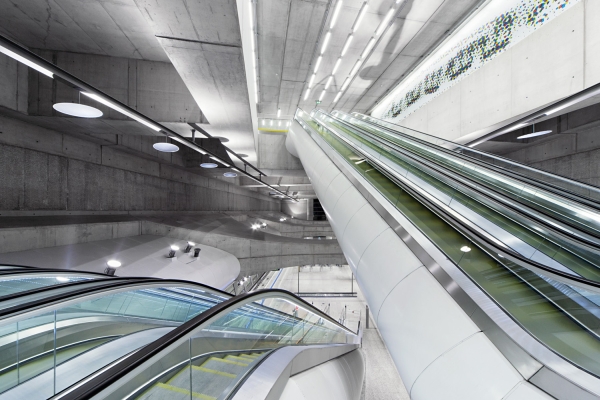

And then the municipal management made a brave decision: the shafts could be left empty. Or rather filled with awe-inspiring visual experience. This is how progressive architects’ teams came to join the project. Accessing the new underground one does not arrive in a traditional tube space where people rush towards the end of the whole through narrow and low channels: here multi-level and multi-storey open and transparent spaces tower above the heads of passengers. Depths and heights open up in every direction, space widens and expands below the surface as if the city regulated into a system of transportation would express its own natural freedom undergound.

Actually, we are deep below the surface: here majestic and large arches of exposed concrete or a multi-layered net of grids strains the space above our heads keeping a delicate equilibrium between the huge weighty mass of the earth and the vast open space. The rails of the underground are already visible during arrival, the protective roof arching above them does not block the sight only provides safety. Freedom and playfulness rule here. The latter is represented by a different artistic component at each station: in Gellért Square it is Tamás Komoróczki’s vortical mosaic with dynamic effects, in Móricz Zsigmond Circus it is powerful panels alternating saturated colours, in Pope Paul John Square on the lateral walls it is finely layered reliefs by György Jovánovics and in Kálvin Square it is the vanishing pixel tracery of the wrap-round surfaces that appear.

And what they have in common at the stops: Anna Baróthy’s poetic glass panels, the elegance and simplicity of the benches and design chairs, the reserved sets of components representing contemporary object design used in a versatile way matched with an inventive utilization of exposed concrete and last but not least the ingenuous bravados of Tamás Bányai’s illumination designs that create generous contemporary spaces reflecting excellent tastes. All these are filtered through by spectacular solutions unknown in Hungary in situations like these featuring such intensive traffic. The spectacles of underground line No. 4 change Budapest’s life from below and yet basically, affecting the visual culture of people living here. When viewed from here the city appears to have stepped into the 21st century.

Engineering establishments of Hungary about 100 or 150 years often generated pioneering architectural achievement as an overall tendency. Excellent examples proving this are the Chain Bridge with the Tunnel, the old and the new Elizabeth Bridge from the 1960s and the cable bridge of Bratislava built by Hungarians in the 1970s. And then there is the most recent Megyeri Bridge, the Mayfly pedestrian bridge in Szolnok, the earlier RC water tower of Margaret Island in Budapest and the more recently built water tower in Budafok. The list could be continued without changing the essence: more often than not, contemporary architecture and engineering innovation tends to go hand in hand like an unseparable tandem in projects nowadays. In underground line No. 4 the artistic image of the stations and the exposed RC structures above them – which appears to be quite contradictory to many people at first sight – are works of art now that equal and rank as integral compositions with unique overall effects and which our descendants may be as proud of as we are of the creations of engineering and architecture listed above.

Kálvin tér, architecture: Palatium Stúdió Kft., photo: Bujnovszky Tamás

A Careful Step Forward – The Underground Station of Line No. 4 Budapest

Architects: FŐMTERV – PALATIUM – UVATERV Consortium

Text: Dávid Bán

Photos: Tamás Bujnovszky

The construction of underground railways in Budapest started with a promising momentum in the very last decade of the 19th century but its next more than 120 years proved to be much more bumpy. Finished on the whole in 1884, Andrássy Avenue preserved its integrity as designers did not allow to spoil it with an above-ground tram service system. Thus a different solution had to be found to serve the millennary exhibition opened in the City Park in 1896. This was the site where the underground system connecting Gizella (today Vörösmarty) Square and the City Park was constructed within less than 20 months as the first of its kind in continental Europe.

In the first half of the 20th century several schemes were worked out in an attempt to keep pace with the dynamic development of the capital ambitioning the extension of the underground railway system – what is even more, by suitingly integrating the already existing urban sections of the railway line, much in the same way as it had been done in Berlin. These plans, however, did not prove to be viable initially because of financial restrictions and later on because of the war. In the 1950s when construction was finally launched, the technology of drilling tunnels was chosen after Soviet examples instead of the former underground. The first part of line No. 2 was opened on April 4th, 1970, after a standstill lasting almost a decade.

This time the capital had elaborated a scheme integrating a total of five lines within which the present-day line No. 2 would have been extended by a feeder line towards Kőbánya, line No. 3 would have covered the distance between Káposztásmegyer to Ferihegy, whilst line No. 4 between the southern part of Buda to Rákospalota. In addition, line No. 5 was also planned to connect Óbuda with Kelenföld drawing a semi-circle on the Pest side.

Elaborating the concept of line No. 4 was started back in 1972. Although the track had been modified several times, the main course remained unchanged. After several decades of adventurous planning, preparation and realization the line finally opened is still incomplete, and needs to be extended in both directions to fully justify its existence. However, 24 years after the opening of the last stage of underground line No. 3, the first 7 kilometres and 10 stations of line No. 4 were finished at last.

The line constructed with tunnel-drilling technology runs deep all along its length without any above-ground stations. All these stations feature central platforms, and are shorter than those of the two previous lines: each is 80 m long. The line between Kelenföld and the Eastern railway station actually connects two railway junctions. The terminal in Buda, which promises the evolution of a genuine intermodal transport hub, integrates direct links between the railway and underground platforms, the two extreme points of the subway provide access routes to the bus and tram terminals towards the suburbs and the centre. Whilst the underpass creates high-standard connections, guiding passengers suitably to the interchanges, above the ground the situation is much more inefficient.

Móricz Zsigmond körtér, architecture: Gelesz és Lenzsér Építészeti Kft., photo: Tamás Bujnovszky

Unfortunately, the Eastern Railway Station project was realised without the appropriate conversion of the surface. Whereas architects wished to transform this transport area into an urban public domain about a decade ago to create a kind of agora, the present-day solution is obviously the result of precipitance. Its single merit is that motor traffic has disappeared from the proscenium of the railway station, but the message of Baross Square has not essentially changed because of the minimal ratio of green areas, street furniture and we—conceived spatial components. It is the irony of fate that the statue of Baross exiled into the background in the 1970 which had marked the centre of the square in the early 1900s was now erected once again in the előter although this time on a curb almost completely separated from pedestrian traffic.

With the exception of three, the stations of underground line connect to the surface almost unnoticed, typically to other areas used by transport or or underpasses which had been built previously. Although this design enables them to integrate into the city’s fabric their accesses are almost hidden because the above-ground information systems tend to be missing opposed to those of the stations which are fairly efficient, practical and well-conceived, disregarding a few minor mistakes. The signs used to inform passengers were designed with strict consistency, and they are actually internationally used schemes which have been simply borrowed: there seems to have been no or little ambition here to create unique forms or playfulness to some extent. The names of the individual stations run along the full length of the platforms and are well visible although their lettering could have been larger. The same holds true of the inscriptions of directions and further stations. However, there are also some fresh design components integrated in the sceheme such as the two different colours showing the safety lanes in two directions and the light strips that flash to inform of the arrival of a train.

General design:

FŐMTERV – PALATIUM – UVATERV Konzorcium

Architecture: Balázs Csapó, Zoltán Erő, Ádám Veres, Zoltán Tóth, László Román, Zoltán Zorkóczy, Klára Szilágyi, Jovanović Biljana – PALATIUM M4 Projekt Kft.

Client: BKV Zrt. DBR Metró Projektigazgatóság

Projekt management: EUROMETRO Kft., BKK Közút ZRt.

Kelenföld-Őrmező:

PALATIUM Stúdió Kft. – Zoltán Erő, Máté Antal, Dóra Brückner, Zsolt Kosztolányi

VPI Építész Kft. – Péter István Varga, Erzsébet Kardos-Karst, Miklós Markos

SZABOTAR Bt. – Tibor Tardos

Bikás park:

PALATIUM Stúdió Kft. – Zoltán Erő, Dóra Brückner, Máté Antal, Katalin Fábry, Zsolt Kosztolányi, Péter István Varga

Újbuda központ:

PALATIUM Stúdió Kft. – Zoltán Erő, Máté Antal, Dóra Brückner, Zsolt Kosztolányi, Péter István Varga

Móricz Zsigmond körtér:

Gelesz és Lenzsér Építészeti Kft. – András Gelesz, Anita Rohr, Tamás Herczeg, László Balázs, László Janesch, Júlia Szendrői, Balázs Miklós Steiner, Attila Gyulai, Eszter Holló, Gergely Molnár-Schád, Péter Safranka

Szent Gellért tér:

sporaarchitects Kft. – Tibor Dékány, Sándor Finta, Ádám Hatvani, Orsolya Vadász, Zsuzsa Balogh, Attila Korompay, Bence Várhidi, Noémi Soltész, András Jánosi, Diána Molnár

Fővám tér:

sporaarchitects Kft. – Tibor Dékány, Sándor Finta, Ádám Hatvani, Orsolya Vadász, Zsuzsa Balogh, Attila Korompay, Bence Várhidi, Noémi Soltész, András Jánosi, Diána Molnár

Kálvin tér:

PALATIUM Stúdió Kft. – Zoltán Erő, Zsolt Kosztolányi, Máté Antal, Dóra Brückner, Katalin Fábry, Péter István Varga

Rákóczi tér:

Budapesti Építőművészeti Műhely Kft. – Tamás Dévényi, Viktor Vadász, Orsolya Máté, Orsolya Takács, Krisztina Németh, István Kovács, Anikó Varga

II. János Pál pápa tér:

Puhl és Dajka Építész Iroda Kft. – Péter Dajka, Zsófia Buzder Lantos, Katalin Füzesi, Judit Szász, Zoltán Szepesi, Katalin Szegedi, Réka Mészáros, Dr. Kitti Kassáné Kalcsó, Ágnes Drabant, Tamás Huszár

Keleti pályaudvar:

Gelesz és Lenzsér Építészeti Kft. – András Gelesz, Anita Rohr, Tamás Herczeg, László Balázs, László Janesch, Júlia Szendrői, Balázs Miklós Steiner, Attila Gyulai, Eszter Holló, Gergely Molnár-Schád, Péter Safranka

Architectural plans:

MÉRTÉK Építészeti Stúdió Kft. – András Reith, Gergely Paulinyi, László Fábián, Péter Sebők, András Hornung, Adrienn Gelesz, Zsolt Nyírő, Andrea Tarjáni, Orsolya Fülöp, Tamás Tákos

STOKPLAN Kft. – György Stocker, Szilvia Bánsági, Attila Horváth, Péter Zsömbörgi, Mihály Nagy, Zsolt Hiri, Tamás Varga, Dániel Beke

Szent Gellért tér, Fővám tér surface:

Dévényi és Társa Kft. – Sándor Dévényi, Márton Dévényi, Iván Halas

Kálvin tér surface:

KÖZTI Zrt. – György Skardelli, András Borbély, László Csízy, László Gáspár, Dávid Petri

Baross tér underpass, surface:

VÁROS-Teampannon Kft. – Lajos Koszorú, Gábor Szenderffy

UVATERV Zrt. – László Pap, Csaba Turján

UNITEF Zrt. – Erika Jurányi

Landscape: Péter István Balogh, Sándor Mohácsi, János Hómann, Máté Pécsi, Borbála Gyüre, Zalán Kuti, Sándor Liziczai, Klára Katalin Pintér, Mónika Radics, Balázs Grábner, Zoltán Nemes

Lights, design, 3D: Tamás Bányai, Balázs Orlai, Péter Kukorelli, Andrea Dúll, Péter Czeglédi, Zsolt Erő

Artworks: Anna Baróthy, Márton Bojti, Andrea Hegedűs, György Jovánovics, Tamás Komoróczky, Zoltán Krizsán-Keszei

Szent Gellért tér, architecture: sporaarchitects Kft., photo: Bujnovszky Tamás