Form Art

Two exhibitions in Vienna

Klimt, Kupka, Picasso and Others – Form Art

Belvedere, 10 March – 19 June 2016

In the late nineteenth century, art based on form took on specific significance in the Danube Monarchy. Subsuming almost an entire cultural region, “form art” was the expression of a special insight and of a collective consciousness. Around 1900, form became the basis from which a wide spectrum of non-representational art developed. In the exhibition Klimt, Kupka, Picasso and Others – Form Art, Hungarian Constructivism, Czech and Slovakian Cubism, and the art of the Vienna Secession join forces for the sake of an enjoyable show.

The exhibition Klimt, Kupka, Picasso and Others – Form Art leads us back to the origins of form, the roots of which lie in mathematics in general and trigonometry in particular. Objects were divided into triangles and then recombined to form concrete or abstract motifs. The unusual importance attached to the teaching of drawing as a form of expression can only be explained in the context of the school system of those days. The exhibition thoroughly examines the similarities and characteristic features of art in the Danube Monarchy; especially when linked to contemporary education and its approach, they illustrate to what high degree education proved formative for a cultural region and its collective consciousness. Franz Serafin Exner, a professor of philosophy in Prague, made the philosophy and pedagogy of Johann Friedrich Herbart known in the monarchy and systematically promoted it with such appointments as that of the aesthetician Robert Zimmermann. Hebart, a German philosopher, psychologist, and pedagogue, was and still is considered the founder of modern pedagogy as an academic discipline. He saw the essential role of a teacher in the task of finding out about a pupil’s existing interests and of constructively relating them to human knowledge and culture. Herbart’s empirical and psychological approach also had an impact on the teaching of drawing. Seen from this perspective, the works of many of the artists in the Danube Monarchy will appear in a new light. The general focus on form may have been one – or even the – central motivation behind the flatness of Viennese Jugendstil and its specific approach to form and frequent employment of geometric shapes. In Vienna it was above all the Secession that disseminated and propagated “form art” (from 1900 onwards) in what was almost a symbiosis with the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts and saw to its gaining international significance.

With an unprecedented accumulation of prominent objects, the exhibition opens up a perspective of the art of the Danube Monarchy that has hitherto been neglected.

Josiah McElheny – The Ornament Museum

MAK, 24 April – 4 February 2016

The Ornament Museum, Josiah McElheny’s installation—developed especially for the MAK—reinterprets the historical design language of Viennese Modernism, finding within it a set of new questions about art and psychology. The New York-based artist, well known for his use of glass with other materials, has created a museumwithin-a-museum—installed in relation to the MAK’s permanent collection of Viennese objects from around 1900.

The pavilion was designed in collaboration with Chicago architect and exhibition designer John Vinci. Its structure and proportion recall Josef Hoffmann’s design for the Austrian pavilion at the Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (Paris, 1925), which helped to spark a new modernist vision. The overall aim of Hoffmann’s pavilion was to point towards his ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk [total work of art] a concept in strong opposition to the purely functional evolution of design.

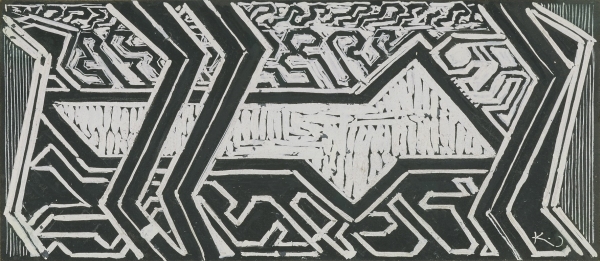

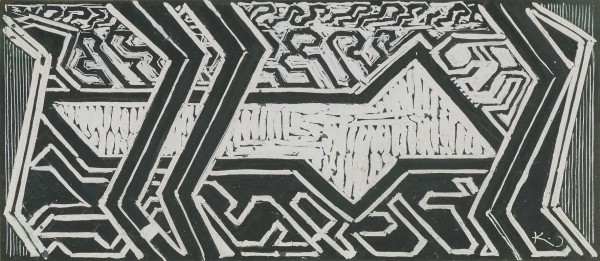

In McElheny’s pavilion, we are invited to enter and look out through the landscapes created by the ornamental motifs on its windows. Produced in collaboration with a specialized glass school using a traditional silkscreen printing technique, these delicate black drawings attempt to translate a number of Koloman Moser’s studies for ornamental form, as in the edition Flächenschmuck [Ornament for flat surfaces], published in Die Quelle [The Source], in 1902. Their ornamental geometry achieves a unique quality by the interplay of graphic shapes and the virtually invisible, shimmering glass surfaces.

With his artistic interest in the use of glass in architecture, McElheny places himself in relation to historical narratives, but also in connection to our current obsession with transparency. In early 1920s avantgarde circles, glass was seen to offer a poetic ephemerality and inspired structures based on crystalline forms intended as utopian models of the future.

The title of the exhibition is borrowed from Paul Scheerbart’s poetic fable about an ornament museum, published in the magazine Die Gegenwart (Berlin, 1911). While inspired by the intensive debates on the aesthetics and meaning of ornament involving Adolf Loos, Josef Hoffmann, and Koloman Moser as well as the art historian Alois Riegl, the project’s dreams are about a different historical confluence as well.

McElheny also hopes to demonstrate a connection to the development of modern psychology in Vienna by Sigmund Freud and others. The ornament of Viennese Modernism was superimposed onto all types of surfaces and media, such as paper, textiles, jewelry, furniture, walls, and architectural elements. As such, it represented the psychology of the society at that time, but it also changed the psychological state of the people inhabiting these almost psychedelic rooms.

The exhibition speaks about the underlying psychology of modern ornament. This language is brought to life through performances in which the actress Susanne Sachsse, as the curator of ornament, offers individual tours of the pavilion, pointing out the hidden visceral meanings of the patterns. The performer wears a fantastical dress, a reconstruction of a 1908 design by Emilie Louise Flöge, the dress becoming an animated ornament itself, connecting the performer’s body, the architecture and multiple, overlapping forms of ornament. This performative approach reflects McElheny’s dynamic ideas about the body’s relationship to looking and to objects, as well as his notion that physical perception is a kind of narration.